Why Hire an Advisor? It’s a No-Brainer

Yes, I happen to be an investment advisor myself but I’ll try to prove to you this is not some self-serving advertisement with links to SIGN UP FOR MY SEMINAR! I see it as a no-BS manifesto for the power of low fees and simple advice. The added value of being an investor with a trusted, reasonably-priced partner in your corner tends to far outweigh the monetary cost of the relationship. It may even be more important now than ever if we consider the outlook for returns in the medium-term. All scenarios below are *hypothetical* and all numbers are *estimates*.

Givens: You need to save money for the future. You need that money to grow faster than inflation if you hope to stick with a reasonable savings rate over your lifespan and still retire comfortably. To get that return above inflation (the “real” rate) you’ll have to be committed to being a long-term investor. I’m going to put this into a simple equation:

Your real returns =

what the market returns

subtract inflation

subtract your errors

subtract fees

subtract taxes

Put another way:

Returns above the rate the bank pays you (today: zero) =

how well global stock and bond markets perform

subtract the gains eaten by the cost of living going up

subtract the things you do to screw up like trading too much, not being allocated properly, or trying to time the market

subtract the costs of your investments and advice

subtract what you have to pay to the government

Visually:

= – – – –

Notice there are a lot of things that subtract from your returns, but none that add to it besides the return from markets? Now you see what I’m getting at and why I’m saying it pays to get someone in your corner. Let’s break it down into things you can and can’t control.

Things you can control: your errors, fees and minimizing taxes.

Things you can’t control: what the market returns, inflation and tax rates.

Your focus should strictly be on eliminating the errors you make, minimizing fees you pay on your investments and for advice, and how to invest as much as possible in tax-deferred or tax-free accounts. No matter how much investors – professional or otherwise – try to fight it, there’s a ton of important stuff out of our control.

Why is it even more important today?

Since we know that valuations around the world are currently elevated, the end of a decades-long bond bull market may be near and global economic growth is estimated to remain slow for some time, it’s more important than ever to maximize our returns because investors may no longer have a strong tailwind of low valuation, low interest rates and strong GDP growth. You can also read “maximize our returns” as “minimize mistakes and wasteful expenses.”

Let’s say a globally diversified stock/bond portfolio of low-cost index funds is expected to return 5% after minimal fund fees per year going forward, compared to a more lofty return of something like 8% as we’ve seen in the past. We must try to get every bit of that 5% as possible because we know that inflation, fees, and taxes are going to dissolve some of that 5% no matter what. In order to harness the power of compound interest, it’s crucial this return is not chipped away any further.

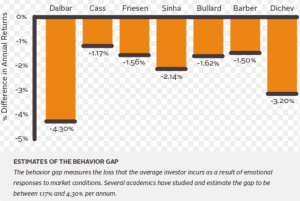

An “average” investor, one with roughly normal intelligence and investing knowledge, may try to get that five percent without help from an advisor – “cut out the fee and do it myself!” Smart, right? Well, not really. We know that the average investor hurts their own returns – those errors we were talking about earlier – to the tune of roughly 2% per year. It’s easier than ever to do something damaging as an investor because there are so many shiny new tools, products, and gimmicks available at the download of an app. The phenomenon of sabotaging our own returns is known as the behavior gap. It’s the difference between what the market returns and what an investor gets after adjusting for doing return-damaging things.

So now a do-it-yourselfer who started with an easy 5% has acted like an average investor and sabotaged their returns and paid a penalty of losing 2% from the 5% they could have had with almost no effort. Now they’re left with a 3% return. But what about the cost of their investment? If they chose active investments – read: expensive – then we can assume the fees they paid on their investments could be around 1% more than passive index funds. Now our investor has a 2% return. I’m also being generous and not calculating the effect that active investments are proven to perform worse than passive investments.

What about inflation? Well, inflation has been averaging about 2% per year and is expected to remain low for quite some time as the economy deals with the potential reality of lower global growth.

Our investor, after seeing a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds return 5%, is now left with exactly ZERO gain in purchasing power for his/her efforts at investing. His/her behavior combined with high fees and inflation has left them no better than a year ago.

So why utilize an advisor? Simple: eliminate the behavior gap and ensure fees and taxes are minimized wherever possible. Instead of a portfolio of active funds, a wise advisor will recommend inexpensive index funds – bringing those fees down from the estimated 1% to around .20% (if not lower). Next, the behavior gap can be reduced, if not eliminated altogether and would add an expected 2% return to an investor’s portfolio each year that would otherwise be hurt by an average investor’s behavior.

Lower fund expenses: estimated savings of 0.8% per year

Eliminate the behavior gap: estimated 2.0% return added

Cost of (this) advisor: .5% per year

Net gain from working with advisor in this hypothetical scenario: 2.3% per year

Conclusion: an average investor, who hurts his/her own returns with detrimental behavior and expensive/underperforming funds may very well be in dire need of professional help (especially) if returns are to be lower than average for an extended period of time. The tailwind of high stock/bond returns will no longer be able to mask these inefficiencies, putting the average investor in a very tough spot. Saving for retirement with a low-to-zero real return will be a tough task to accomplish if an investor decides to go it alone.

Even shorter conclusion: keep fees low, hire somebody to stand between you and bad decisions.

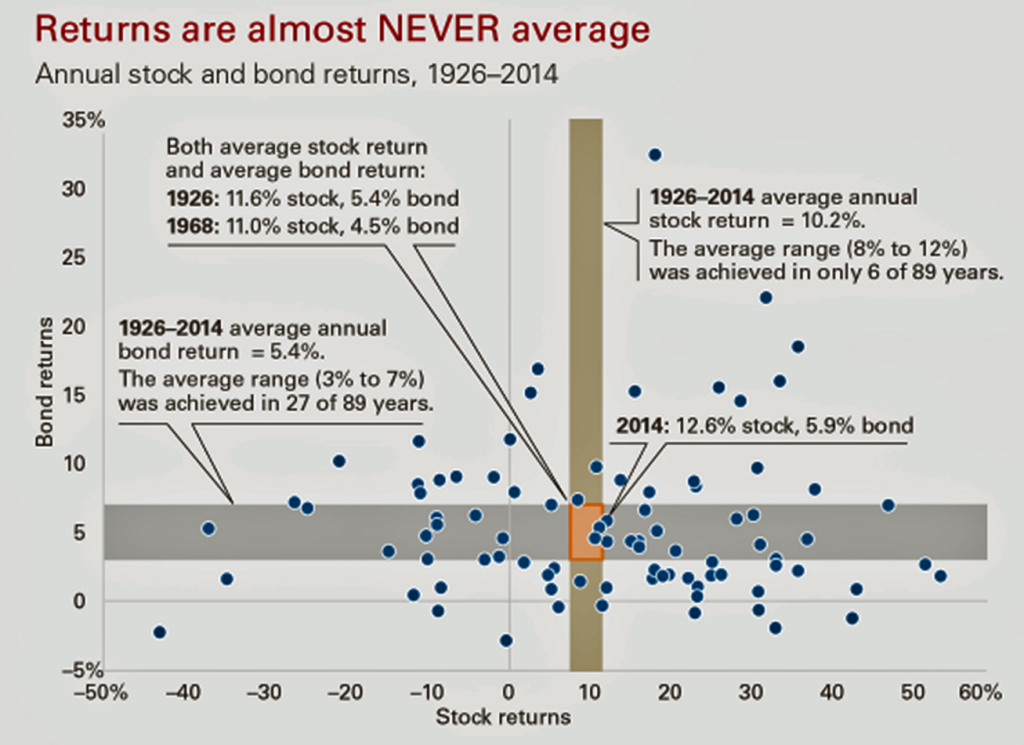

A Shotgun Pattern

This data from Vanguard is so good it requires its own post. “Average” is what all long-term investors can expect to get over the span of decades, but at the same time they’ll rarely get what’s considered to be normal on a yearly basis! Such an important concept to explain:

Newton’s Law of Finance

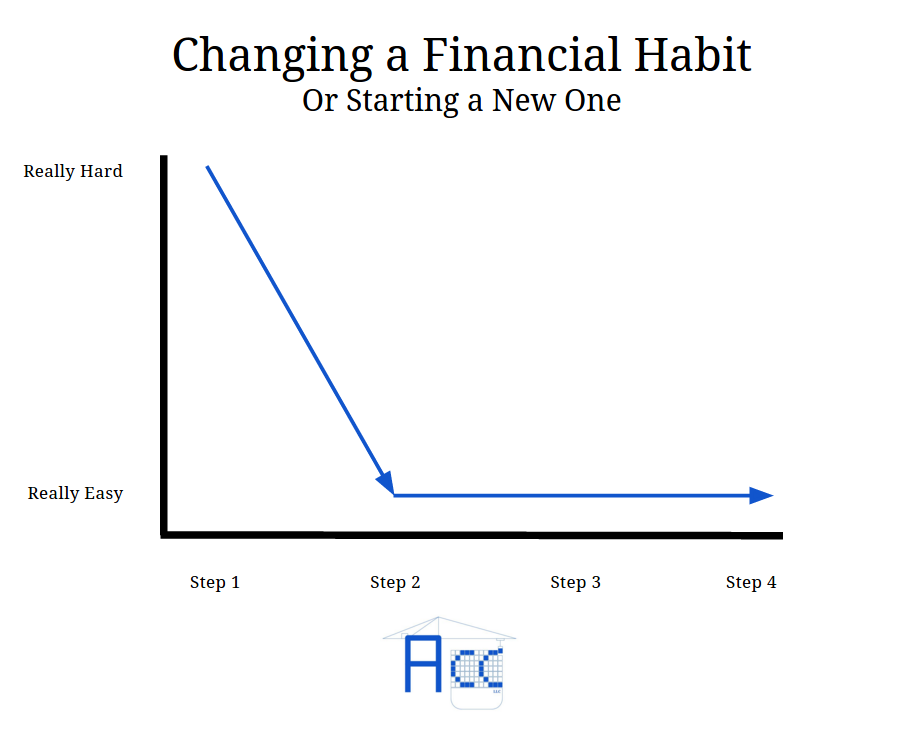

It’s really hard to start a new financial habit and in some cases it’s even harder to change one already in place. We have routines, tendencies and grooves worn in the pathways where our money flows. After all, it’s basic physics: an object in motion will stay in motion unless acted on by an outside force. Your habit is that moving object and sometimes it’s necessary to take action and change its direction, or to stop it completely.

Changing habits is not an easy task but this simple chart shows it gets much better after that first step. Since money triggers such emotion in most people it’s understandable we take great effort to avoid making decisions and changes. The bright side: the first step is just like any other task at its core. The worst step of getting a nagging toothache fixed is making the appointment, right? Once the appointment is made, it’s all downhill from there – usually it’s the time spent thinking about committing to get to the dentist that brings the most anxiety instead of the procedure itself. The same goes for financial habits. From opening a new high-yield savings account, to logging in to bump up a 401(k) contribution, or scheduling auto-pay to reduce a loan balance, the hardest part of a positive financial habit really is the first step.

I’ll bet you nearly every single Step 1 in the hopper takes two minutes or less!

Risk Tolerance, and an Offer from Riskalyze

Let’s get this out of the way first: this is a post targeted more towards advisors and was inspired partly by a conversation on Twitter. Nerdy terms and opinions will follow. What this ISN’T, is an attempt to offend anyone at Riskalyze, or its users – both groups are trying to do what they think is best for clients (just like I am).

Assessing risk tolerance is an absolutely vital, and legally required, task among RIAs, but how we get there is a point up for debate. Risk tolerance software is all the rage right now, but I’m not sold on its advertised use case. From my view, the software is treated more as a means to generate “sales” and also as a way to check off a compliance need.

My definitions, with regard to all things Risk Tolerance:

Static approach – an advisor will base portfolio decisions based off of a single point (or points) in time after a client answers a risk tolerance questionnaire. In my eyes, the level of customization within a questionnaire doesn’t provide value. It’s still a questionnaire – subject to the whims and wild, short term oscillations of human emotion. A questionnaire taken at 6:01pm today, could be completely different than a survey taken at 6:21pm today, all else equal. An advisor using a static approach to risk tolerance, and its subsequent effect on portfolio management, may be naturally inclined to accommodate with their suggestions and advice according to questionnaire results. Accommodation makes it easier to give clients what they *want* instead of what they *need* and the static approach is advertised as more efficient because it cuts down on the time spent with clients. Cutting corners in the name of more sales today is not a wise way to generate long-term business – in my opinion, of course.

Dynamic approach – an advisor recognizes risk tolerance is amorphous and slippery and can only be assessed over the long-term, through multiple interactions and many different market environments. Assessing long-term risk tolerance doesn’t mean taking the same questionnaire numerous times. A long-term approach to risk tolerance means the advisor is trying to make a best-guess attempt at an ultimately subjective and volatile piece of information (read: not quantifiable as a single point on a 1-99 scale). A dynamic approach to risk tolerance is much harder because it involves educating a client after having numerous conversations in a years-long process and after observing her behavior, instead of accommodating simple questionnaire results. The dynamic approach takes time and has no immediate financial reward to the advisor like a one-and-done risk number might provide. Is there really a tangible difference between a 42 and a 43? The “It’s That Easy!” message just doesn’t resonate for an advisor taking the dynamic approach. At the absolute core of the dynamic approach is a relationship.

My conversation on Twitter started with a comment I made about Riskalyze, a provider of risk tolerance software for advisors. Their CEO, Aaron Klein, got into the mix for some debate. The tweet was shared by Advisor Tech Guru Extraordinaire Bill Winterberg, and he tagged some prominent Riskalyze users. Thanks, Bill? Anyway, my thoughts aren’t meant to be directly critical of anyone’s use of Riskalyze – if they feel it brings value to their clients, that’s fine! – but I’m trying to explain why I don’t use this kind of software and why I used the term “shtick.”

As I told Aaron, I don’t think he and his company have bad intentions. They want to help RIAs succeed. My main point is that I think they try to sell something I view as having dubious merit, and I think they go about it in a strange way. It doesn’t mean using the Riskalyze approach is evil or tries to skirt a fiduciary touch. An RIA using Riskalyze is without a doubt better for a client than using a broker. I’ll try to explain a little more about my personal experience below.

I made the comment that I was “annoyed by their whole shtick” because I went through the process of trying to evaluate their offering and their sales people keep calling/emailing me (*more on that later). While I was kicking the tires about a year ago, the process just rubbed me the wrong way, compounding my doubts about their offering I had in the first place.

I view these testimonials as Broker-speak, but your opinion may vary:

First, they offered no demo environment, no way to actually try the product for a limited time. This is not the norm in the “fintech” RIA vendor world – or at least with the many, many offerings I’ve tried out. Why can’t I try the product out, like the rest of your industry-mates allow? To me this type of policy usually raises a red flag. What if you couldn’t test-drive a car from the dealer before a purchase? Even Tesla does a test-drive. If this has changed, please let me know, Riskalyzers.

Second, the language and sales pitches used, to me, oozed of the short-term focused, sales-metric-touting lexicon of a broker culture versus the more long-term focus RIAs typically desire. I’m completely paraphrasing here, but the sentiment in a demo video was similar to “Advisor Dan increased his close rate to 95% after the first month of using Riskalyze” or “Advisor Sally brought on a million dollar client after showing her Risk Number.” The pictures above are pretty similar. If I view risk tolerance assessment as a subjective undertaking that requires a heavy emphasis on client education and time, then touting a quantitative approach built on “Nobel Prize-winning science” is probably not going to be my thing. (Sometimes Nobel Prize-winning science is best left in the laboratory)

Science is an interesting term to bring up and it probably encapsulates the debate perfectly. Risk tolerance, and its parents Ability and Willingness to take risk, is best viewed as art – not as science. As advisors, one of our biggest tasks (if not the biggest) is minimizing the behavior gap and that involves being knee-deep in the behavioral trenches of investing – an approach I believe is best left for words, time and conversations with the emotional, human being clients involved. Including an Investment Policy Statement, which records and lays out all changes in client willingness and ability to tolerate risk lays the groundwork for “behavior gap: zero.” Risk tolerance is not, in my opinion, a number between 1 and 99.

Quite simply, if I’m on the fence about the use case, I don’t like the way they sell the product, I can’t try the product out in a trial and they use broker-ish and sales-y terminology throughout, then I don’t feel there’s much else I can say to explain my point of view here.

If taking this stance means I have to eschew whatever short-term benefits I may get from using a static assessment approach, or I have to take a contrarian opinion on the subject, then so be it.

Friday edit: you can get your own Riskalyze Risk Number in about 30 seconds, by using one of the links on any number of advisor sites. Just search for “Riskalyze Test.” Is this really the way advisors should be framing investing? It’s not blackjack! The quickest way to having mismatched expectations is to start quoting return numbers, up or down, derived from a short period of time:

*More on my recent contact with the Riskalyze team (some sarcasm may be present):

They reached out to me yesterday with curious timing – it was Fed Day™ – as well as today with an email and a call directly after to follow up. The Riskalyze sales guy was seeing if I wanted to “stress test” any portfolios for a 25bps rise in interest rates. Now, nothing wrong with that on the surface, right? It’s nice to see they’re concerned about my portfolios! That’s so nice of them. But what if I already have suspicions about Riskalyze being more “broker” than “RIA” and what if I already suspect the merits of the services they offer? Then I guess you’d understand how I’d take exception to the offer with even more reason now:

Offering to test one of my portfolios against an interest rate hike on Fed Day is a blatant attempt to play on my Fear of the Unknown because the big, bad Federal Reserve was surely going to cause massive reverberations with its first interest rate hike on Wednesday. Yes, you’re right, Riskalyze, I must indeed test and take action based on short-term market movements, and how did you know I was vulnerable to sales pitches on this emotional day?! If you think I haven’t considered the duration profile of client accounts and if you think you’re notifying me on Fed Day of the “danger” of rising rates, then you are mistaken.

I can plug in a portfolio to Excel, throw in some duration numbers and calculate the effect of any interest rate movement I dream, in about five minutes. Were you thinking advisors didn’t have this ability? Thanks, anyway, guys. RIABiz wrote a great piece about this sort of thing – and I fully agree with Brooke Southall’s sentiment, and I believe it translates perfect to the Riskalyze portfolio stress test offer. An offer to “stress test a portfolio” on Fed Day, because I surely must be a reactive and active-focused advisor who is influenced by daily oscillations, is an insult to my intelligence. Get this stuff out of here, Riskalyze, or direct it to the broker world. This garbage is for the active managers of the industry, for the watch-spinners and for sell-side, CNBC-watching lemmings working in the wirehouses.

Brooke says it far better than I can:

“The group that continues to refuse — deliberately, if not willfully — to get it is those providers of picks and shovels to RIAs — vendors. Either they are selling the wrong product, selling it in the wrong spirit or marketing it in the wrong way.”