There is nothing more fundamental to a healthy financial life than a fully stocked emergency fund. And there are many guides to emergency funds, but this one is mine.

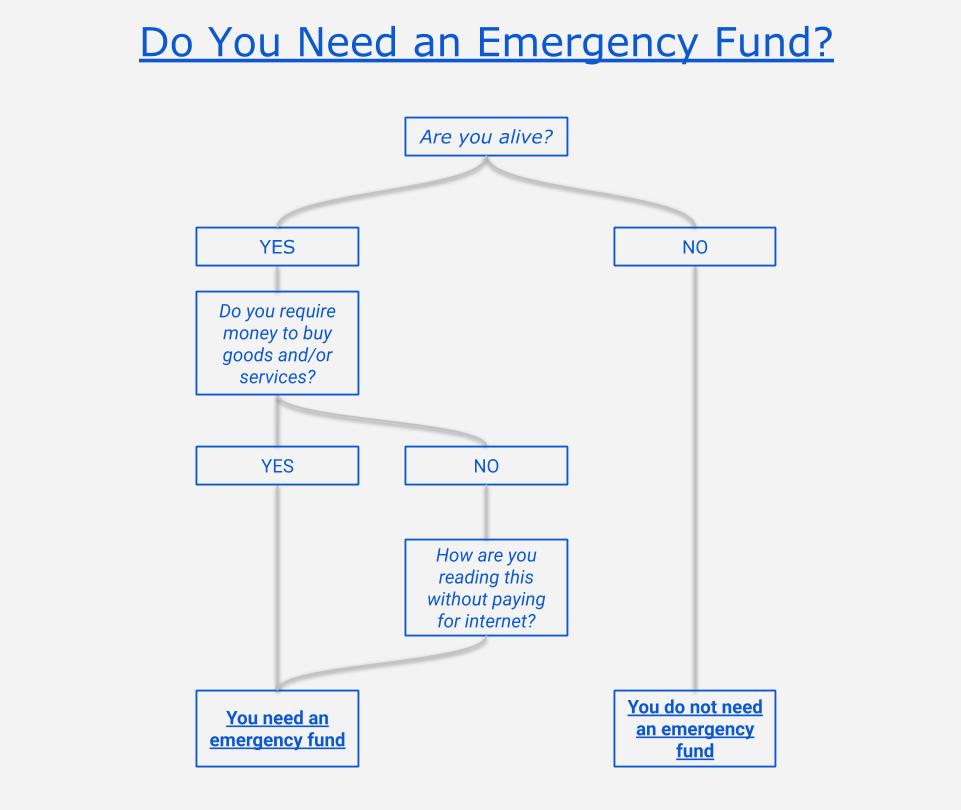

Do you really need an emergency fund?

Some people like to think they’re immune from needing an emergency fund, giving reasons like “I’m retired” or “I have too much debt” or “I’m ridiculously wealthy” or “I have a very stable job and no debt” or “I live in self-sustaining bunker.”

But let’s get down to the definition of what an emergency fund actually is:

An emergency fund is simply a stash of money you only touch in cases of, well, emergency. (More on the definition of “emergency” later)

This means all of the above excuses are rendered moot.

- Retired people need a stable, liquid pool of money in case any number of things happen – like large healthcare expenses – and especially as a buffer from feeling emotional about short-term market swings.

- People deep in debt need an emergency fund because it’s simply the first step in the process of emerging from a negative net worth to a positive net worth. (True, it’s the same as saying, somewhat obviously, that they need to be out of debt)

- “Ridiculously wealthy” people need an emergency fund because it’s a vulnerability to have all assets tied up in investments or illiquid property.

- People with stable jobs and no debt need an emergency fund because a stable job is only as good as the economy, industry, or government their occupation serves.

- The bunker people are already proving my point because their whole shelter is an emergency fund full of, presumably, dry goods and ammunition.

An emergency fund primarily functions as an immunization from all of the possibilities that everyday life brings all of us at one time or another. This would be the “lovey blanket” factor, as I like to call it. An emergency fund is a comfort in the face of uncertainty.

Most importantly, you need to be able to survive today to be able to plan for tomorrow. An emergency fund is key to that survival.

So, we’ve settled it. Everyone needs an emergency fund.

How much money do you need to keep in an emergency fund?

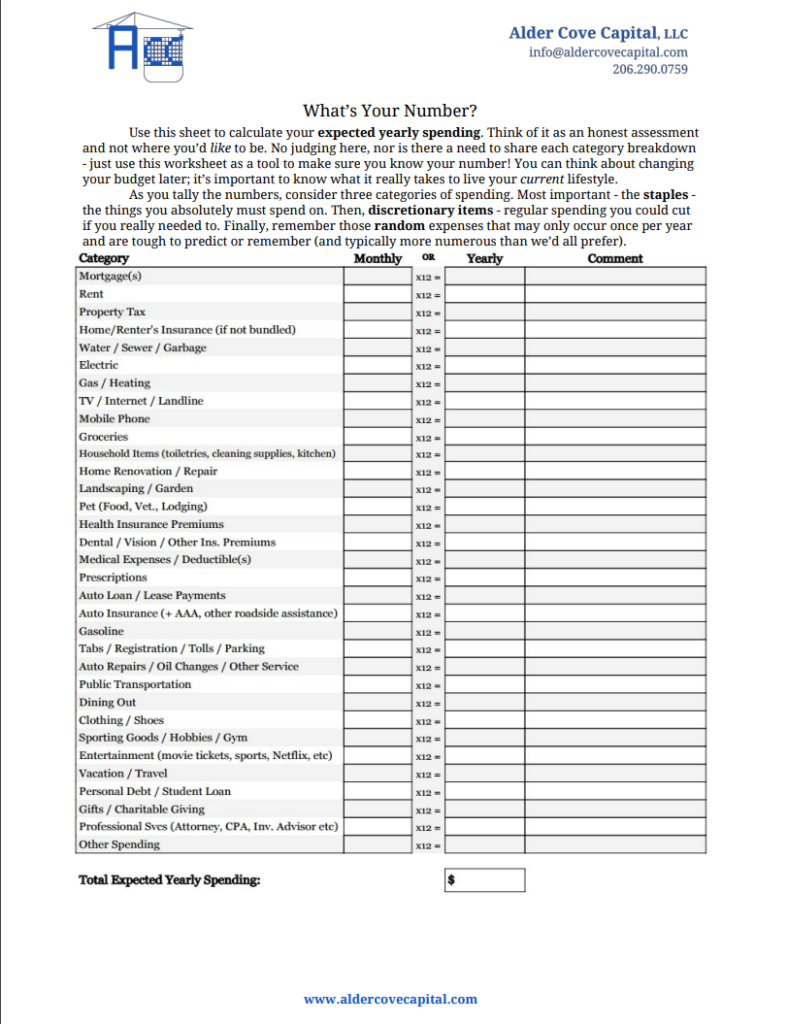

There are many different rules of thumb, but I generally recommend keeping three to six months’ worth of expected annual spending as an emergency fund, which translates to 25% to 50% of what you expect to spend annually on an ongoing basis.

This means you’ll need to know how much you expect to spend. You can figure out this number by using my one-pager here, or create your own copy in a digital version here. And don’t turn it into a budget – just an honest assessment.

Three to six months is a guideline, but given that the average length of unemployment is currently about five months, I definitely don’t recommend going less than three months because that puts a heck of a lot of pressure on someone to get a new job in the event of a disruption of employment or a very large unexpected expense.

Factors encouraging a larger emergency fund, all else equal:

- High debt levels relative to income

- Having dependents

- Known health issues

- Working in an economically-sensitive industry (businesses more likely to rise and fall in cycles)

- Unpredictable patterns of income, and/or when self-employed or working for a smaller company

- Having a low savings rate

- Having a low risk tolerance

- No disability insurance in place

- High deductible health insurance

- Inadequate home/auto insurance coverage

- Concentrated investment positions (non-diversified portfolio)

Factors encouraging a smaller emergency fund, all else equal:

- Low debt relative to income

- No dependents, or having a two-income household

- Good health

- Working in a stable industry (think healthcare, education, government)

- Salaried income or pension/annuity income

- Having a high savings rate

- Having a high risk tolerance

- Sufficient disability/auto/home insurance

- Low deductible health insurance

- Diversified investment portfolio

Where should your emergency fund live?

Simple: A high-yield savings account, most likely in an online-only format to get the best rates. Here’s an example of the difference between the average rates offered by online and in-person branches over the last five years:

After a years-long marathon of interest-free deposit accounts, we’ve finally made it back to the world of getting a decent rate of return on savings products. It might not last long, but right now you can get a 2% annual yield with many reputable institutions.

Paying a decent interest rate is important because this will allow the account to at least have a chance at keeping up with inflation. Plus, free money is nice. A $50K emergency fund will produce $1,000 in interest per year right now. That’s not nothing.

Just make sure the account is FDIC-insured (or NCUSIF at a credit union). Also confirm your account doesn’t exceed deposit insurance limits (generally $250K) – but most people won’t have to worry about this for an emergency fund.

To compare accounts, Bankrate and NerdWallet have pretty good screeners.

What constitutes an emergency, anyway?

This is the really subjective part. You could say I’m an emergency fund fundamentalist, because I don’t believe in using the account as a slush fund. There are only a few reasons you should ever take money from this account:

- Job loss

- Paying for a high medical insurance deductible or coinsurance

- Any incidents/accidents that can’t be reasonably (or aren’t) covered by insurance*

That’s it.

No, not that other thing you just thought of. Only job loss, medical deductible/coinsurance, and only the craziest random things.

This is not a stash to be raided for vacation, (especially not) for buying a home, for home renovations, for buying a car, for fixing a car, for getting a new roof, for yada, yada, and/or yada.

Let’s talk about that “*” above. The phrase “can’t be reasonably covered by insurance” is an important one. Most of these instances will end up with the final verdict of “you should have allocated for that in your expected spending” via insurance premiums or deductibles. This means, for instance, that having to spend a chunk of money for auto insurance deductibles or auto maintenance should be planned for. Or your insurance policies should be structured so that a paying a deductible doesn’t necessitate emergency-like spending.

Why not a new roof? Simple: Replacing a roof shouldn’t sneak up on you. It’s an expense that should be planned and saved for over the span of years. Now, a random roof leak would be different. It certainly would be unexpected and should be considered an emergency because it’s unlikely that homeowner’s insurance will cover it if it’s normal wear and tear or negligence (it also needs to be urgently fixed).

A lot of this comes down to your expected annual spending. If a spending item falls into any of the categories listed on the sheet I provided, it probably will be denied from being bailed out by your emergency fund. Own a home? You better be putting a huge number down for “Home Renovation / Repair”. Same in the auto category: If you own a car and leave “Auto Repairs / Oil Changes / Other Service” blank, then you, my friend, have built a BS Budget.

Biggest of all, your “Other Spending” category sure as hell better not be blank. That’s where you allocate for all the random spending that would be impossible to predict – and it’s not unreasonable to have it equal 10% of your expected annual spending.

Your emergency fund has two best friends

Insurance is the key to stabilizing the firewall around your emergency fund, but it’s also aided by keeping a healthy “float” in your checking account.

First, insurance allows you to hedge against most of the low-probability / high-cost events you could face (death, disability, flood, fire, earthquake, theft, burglary, severe illness, car accidents, even lawsuits or professional liability – the list is long).

Second, a healthy float in your checking account will allow you to pay for some the random non-emergency items that arise. This lowers the tendency to run to the emergency fund for a quick buck. Simply take your expected annual spending and divide by 12. You should seek to have a month’s worth of spending remaining in your checking account at all times. For a household expecting to spend $90K per year, this buffer should be set to roughly $7,500. After all the normal bills are paid, this buffer will finance things like the random new bumper, new oven, or tickets to the Hawaii trip. If your checking balance goes below one month or above two months of spending, then it’s time to re-calibrate.

How do you build an emergency fund from scratch?

Yes, it’s daunting. If you don’t have the funds to just throw a huge chunk of change over to a high-yield savings account, you might see this as an impossible task.

Two steps will aid in fully funding your emergency fund:

- 1) Treat it as an expense: Choose a date you think you can reasonably get the account fully funded. If that day is three years from now, then a monthly expense for your emergency fund is the equivalent of 1/36th of the fully funded value. (A $30K fund would need roughly $833 in monthly deposits to reach its goal in 36 months)

- 2) Automate: This part will create a forced commitment to the step above. You’re more likely to keep to the goal of forced saving if it’s something you have to turn off to disrupt. Get the courage to set up an auto-deposit and commit to treating it as a fundamental necessity to your annual spending. Nothing will get you to truly consider other spending than automating this step.

We’ve covered why you need an emergency fund, how much to keep there, where it should live, when it’s OK to spend from it, and how to begin building one. Anything you think I missed? Questions about emergency funds? Let me know your thoughts.